On August 11, 2025, Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) legislator Huang Kuo-chang formally announced his candidacy for the 2026 New Taipei City mayoral election. Speaking with deliberate ambiguity, he remarked that he had “never ruled out the possibility of the opposition jointly supporting the strongest candidate.” While this might sound innocuous, it was in fact a political shockwave for the New Taipei race. For the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Huang’s move not only adds another competitor but could also serve as a catalyst for KMT–TPP cooperation, potentially altering the political landscape of not just New Taipei, but local elections nationwide.

Although the KMT and TPP have cooperated in past recall efforts, such cooperation may, in the long run, prove to be “single-benefit” rather than mutually beneficial—serving one side more than the other. The TPP has long positioned itself as a “reformist force beyond blue and green” on Taiwan’s political spectrum. Yet in recent years, from legislative behavior to local issue stances, its policy alignment with the KMT has led outsiders to question whether the TPP is drifting toward the blue camp. Huang’s mayoral run could, on one hand, use the TPP brand to appeal to centrist voters, while on the other hand, echo KMT positions on certain issues—leaving room for cooperation talks between the two camps. For Huang, running may not necessarily be about winning outright, but rather about leveraging his candidacy as a bargaining chip. If the KMT and TPP decide to unite at the last moment, Huang could trade his high polling numbers for a vice mayoral slot, policy concessions, or future cooperation in legislative elections. His skill in “leveraging the old to bring in the new” is already evident; under the recently activated “two-year rule,” TPP legislators have been replaced with new faces—moves that could benefit his electoral ambitions by currying favor with fresh lawmakers.

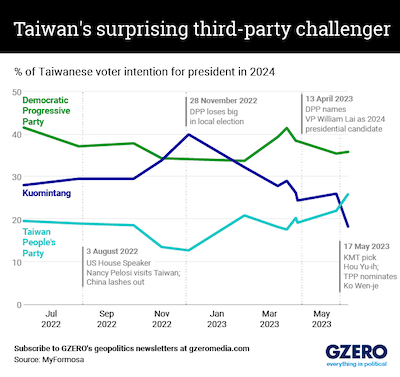

Given Ko Wen-je’s failed attempt at a KMT–TPP alliance during the 2024 presidential race, any cooperation in New Taipei will proceed with extreme caution. Mutual trust between the two camps is based more on shared hostility toward the DPP and political interests than on genuine alignment. On the surface, such cooperation appears mutually beneficial: the KMT could gain middle-ground and youth votes, while the TPP would obtain local resources and organizational strength, increasing their combined chances of defeating the DPP candidate. However, structurally, this arrangement leans toward “single-benefit,” with the advantage tilting heavily toward the KMT.

From a vote-base perspective, the KMT’s support in New Taipei far outweighs the TPP’s. Even in a united front, the KMT would still hold the dominant position, and the TPP could end up relegated to a supporting role. In the long term, the KMT could absorb TPP supporters, but the reverse transfer is limited—gradually diluting the TPP’s brand and weakening its independent viability. The history of KMT–PFP cooperation shows that alliances often involve talent poaching. Beyond resource disparity, cross-strait relations still anchor the KMT’s political consensus with Beijing, leaving the TPP as little more than a pawn to counterbalance the DPP. Who ultimately uses whom remains an open question.

Moreover, the KMT has long held the misconception that young voters are loyal to Ko Wen-je and the TPP. In reality, youth votes are highly fluid, often driven by opposition to the ruling party rather than steadfast party allegiance. This leads to frequent overestimations of support rates. Given the last failed KMT–TPP cooperation, it remains uncertain whether a “vote abandonment” effect would occur in a local election. The KMT, with its stronger local foundation, has little necessity to concede New Taipei. Otherwise, it could risk “raising a tiger to invite trouble,” as the DPP once did with Ko Wen-je—only to later be abandoned.

As for the DPP, it must remain vigilant. The current dynamics could easily evolve into a three-way contest. But overplaying its hand could prompt the KMT and TPP to join forces against it, thereby strengthening their unity. In such an uncertain and fluid situation, a low-profile approach may be the wiser strategy.

Looking at the broader picture, the New Taipei mayoral race is unlikely to be a straightforward KMT–DPP showdown. Instead, it is shaping up to be a strategic three-way contest among the KMT, DPP, and TPP. The DPP will likely anchor its campaign narrative on municipal governance issues. If the race escalates into a partisan battle, the DPP risks being dragged into the KMT–TPP agenda, especially if Ko Wen-je “comes out of seclusion” and turns the local election into a theater of political resentment—causing the real issues to fade from focus.